Perceptions of Conflict in Kawe

Context

In late October 2015, Tanzanians went to the polls to vote in the most competitive elections to the ruling party’s dominance since independence. Uncharacteristic of other Tanzanian elections, the 2015 elections experienced some localized conflict between opposition voters and security forces, particularly in urban constituencies. Kawe Constituency is one such area where conflicts occurred. The conflicts that occurred were not of a lethal nature and mostly consisted of tear gas and other riot disruption techniques. What is significant about these conflicts is that they show an increased willingness by the incumbent party to utilize security forces to benefit their party. Additionally, the ruling party challenged the results of the vote count in Kawe Constituency, which resulted in the incumbent opposition retaining her seat by a margin of 7.4% (The Citizen 2015). Despite the widespread media attention (The Citizen 2015; Mawenya Forthcoming; LHRC & TACCEO 2016l TEMCO 2016), perceptions of the severity and even the occurrence of the conflict are varied.

Given the varied responses, this study seeks to understand why perceptions of electoral conflict vary within locations that experienced conflict.

Theory

In Americanist partisan bias theory, perceptions of political events are influenced by partisan identification for low-salience topics (Bartels 2002; Bullock et al 2013; Campbell 1980; Wlezien, Franklin & Twiggs 1997; Fiorina 1981; Lewis-Beck Nadeau, & Elllias 2008). Another component is the length of affiliation with a party, meaning that the longer a voter supports a party, the stronger their bias will be (Bartels 2002; Fiorina 1981) The justification is that voters seek to present their preferred party in a positive nature (Bartels 2002; Brennan and Lomasky 1997).

It is not clear from existing work whether these findings translate to newer democracies, though the following authors provide evidence that it may (LeBas 2011; Carlson 2016; Brader & Tucker 2002; Mainwaring & Zoco 2007; Dalton & Weldon 2007). Furthermore, topic salience does not have a robust literature, with some authors providing preliminary evidence to partisan bias in high-salience topics, such as civil war and government-sponsored killings (Kalyvas 2003; Bratton 2011).

Other than partisan bias, respondent censoring may occur on a politically salient survey with the presence of a guide from the incumbent party (Afrobarometer 2014). To address this, I control for the presence of a guide and add an interaction between the presence of a guide and support of the opposition. The theoretical rationale for the interaction is that an opposition support might be reluctant to express their opinions of a violent event involving the ruling political party if a member from that party is in the area guiding the enumerators.

Hypotheses

If voters seek to represent their party is a positive way and the conflict that occurred in Kawe was between the state’s security forces and opposition voters, I expect to see:

H1. Voters supporting the opposition coalition to perceive more electoral conflict than voters supporting the incumbent party.

If long-term affiliation with a party is key for voters displaying bias and Tanzania has only had multi-party elections since 1994, I expect that:

H2. Older voters will perceive more electoral conflict than younger voters.

Methods

I utilize an original survey of 152 respondents in Kawe Constituency measuring security provision and social attitudes. The surveys were conducted in Swahili or English at respondents’ homes by two University of Dar es Salaam graduate students with experience in enumeration. The enumerators conducted four surveys per each enumeration area simultaneously.

The dichotomous dependent variable in the logistic analysis is respondents’ perception of conflict in the community during the election. The independent variables, which correspond to the hypotheses are: respondents’ self-reported partisan affiliation and self-reported age. Controls include education, wealth, gender, and religion. I also control for the enumerator who conducted the survey and the presence of a guide from the incumbent party being present.

Key Findings

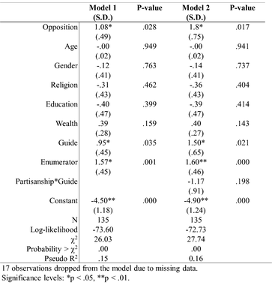

I apply logistic regression in both models, with the only difference being the addition of the interaction variable between partisan affiliation and a guide from the ruling party in the second model. Both models are below.

Because coefficients in logistic regressions are difficult to interpret, I run estimated marginal effects in the figure below. What this test displays are the estimated effect of a variable on a scale of 0 to 1 with all other variables in the model held at the mean values. Figure 2 presents the estimated marginal effects of the second model. The red line represents an effect of 0. The black bars are confidence intervals at 95%, and the blue dots are the estimated marginal effect of each variable with all others held at means.

I find evidence to support a partisan bias explanation of perceptions of conflict. Those who support the opposition are 38 percentage points more likely to say there was violence in their constituency, significant at the 5% level. Age is not significantly correlated with perceptions of violence, refuting hypothesis two.

Other effects, particularly those of enumerator and guide are not part of the original theory but I interpret to mean that an unknown factor about one of the enumerators primed respondents to report or not to report conflict. Moreover, I interpret the sign of the guide present to indicate that the incumbent party wanted conflict to be seen, but only as a product of opposition discontent and thus legitimizing the actions of the security forces and downplaying the severity of the incidents.

Future Research

With additional evidence supporting a partisan bias story, future research should address where these partisan effects come from: different experiences, different media consumption, motivated reasoning, partisan cheerleading, or willing negligence.

Significant differences in perceptions of conflict during the most contested elections in Tanzanian history present a cause for concern. Particularly over the representation and perception of violent political events associated with the ruling party.

Findings provide additional support for a growing body of work on partisan bias in new or weak African democracies.

Notes

I would like to thank the Africana Research Center, African Studies Program, Department of Political Science, and Student Engagement Network for funding this research trip.

Author: Seamus Wagner